In the early hours of September 11, a dispatcher with the sheriff’s department in Dallas County, Iowa, spotted something alarming on a surveillance camera in the county courthouse. Two men who had tripped an alarm after popping open a locked door were wandering through courtrooms on the third floor, she reported over the radio as deputies raced to the scene. The intruders wore backpacks and were crouching down next to judges’ benches. When the first deputy pulled into the parking lot, the men moved to an open area outside the court rooms and concealed themselves.

“They were crouched down like turkeys peeking over the balcony,” Dallas County Sheriff Chad Leonard said in an interview. “Here we are at 12:30 in the morning confronted with this issue—on September 11, no less. We have two unknown people in our courthouse—in a government building—carrying backpacks that remind me and several other deputies of maybe the pressure cooker bombs.”

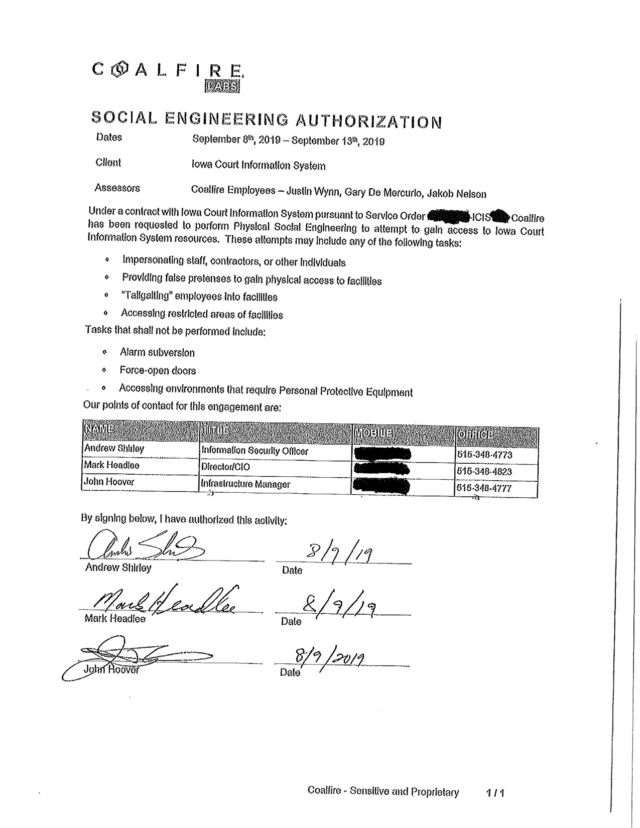

After more deputies arrived, Justin Wynn, 29 of Naples, Florida, and Gary De Mercurio, 43 of Seattle, slowly proceeded down the stairs with hands raised. They then presented the deputies with a letter that explained the intruders weren’t criminals but rather penetration testers who had been hired by Iowa’s State Court Administration to test the security of its court information system. After calling one or more of the state court officials listed in the letter, the deputies were satisfied the men were authorized to be in the building.

The deputies listened with interest as the pentesters—who work for Westminster, Colorado-based Coalfire Labs—explained how they got in. They said they found a courthouse door unlocked. So they closed it from the outside and let it lock. Then they slipped a plastic cutting board through a crack in the door and manipulated its locking mechanism. (Pentesters frequently use makeshift or self-created tools in their craft to flip latches, trigger motion-detected mechanisms, and test other security systems.) The deputies seemed impressed.

When Leonard arrived on the scene, the mood quickly changed. Leonard read the letter and sized the men up. It said the men were authorized to perform “physical social engineering to attempt to gain access” to courthouse systems. The attempts could include:

- Impersonating staff, contractors, or other individuals

- Providing false pretenses to gain physical access to facilities

- “Tailgating” employees into facilities

- Accessing restricted areas of facilities

The letter also listed tasks that should not be performed, including:

- Alarm subversion

- Force-open doors

- Accessing environments that require personal protective equipment

The pentesters had already said they used a tool to open the front door. Leonard took that to mean the men had violated the restriction against forcing doors open. Leonard also said the men attempted to turn off the alarm—something Coalfire officials vehemently deny. In Leonard’s mind that was a second violation. Another reason for doubt: one of the people listed as a contact on the get-out-of-jail-free letter didn’t answer the deputies’ calls, while another said he didn’t believe the men had permission to conduct physical intrusions.

The sheriff also said he and his deputies smelled alcohol on the breath of one of the men. (Leonard, who didn't identify which Coalfire employee it was, said a test later showed the pentester had a blood alcohol content of 0.05, the equivalent of one or two drinks. It is below the 0.08 threshold for an operating while intoxicated conviction.)

Leonard promptly had the men arrested on felony third-degree burglary charges. They spent the night in jail in separate cells, where one of them was given a bench with a sleeping pad. After being arraigned the following morning, they were shocked when they were once again returned to jail. The pentesters weren’t released until late that afternoon or early that evening on $100,000 bail ($50,000 for each).

The charges have since been reduced to misdemeanor trespassing charges. Trial is scheduled for April. Meanwhile, the sheriff’s department in nearby Polk County is conducting a criminal investigation into a September 10 break-in on its courthouse under the same arrangement with the State Judicial Administration.

Cause célèbre

The case has become a cause célèbre that has galvanized a variety of different interests. For Coalfire and professional pentesters around the world, the charges are an affront that threatens their ability to carry out what has long been considered a key practice in ensuring clients’ systems are truly secure. If pentesters can’t be confident that physical assessments won’t result in criminal prosecutions, security professionals say they’ll no longer be able to carry out this core function with the vigor and thoroughness it requires.

“This does affect my job directly,” said a penetration tester who asked to be identified only by his handle @Tinker. “This affects physical pentesting in general and it really affects government pentesting when the state government can’t provide protection and you can’t trust the state government to stand behind its own laws.”

For Dallas County officials, on the other hand—and possibly officials in nearby Polk County—the case is about their sovereign right to police their tax-payer-owned facilities. Leonard said that Iowa’s State Court Administration, or SCA, didn’t have the legal authority to permit the men to force their way into the county-owned building.

What’s more, the sheriff said the pentesters’ use of lock-picking gear and their alleged tampering with an alarm system—again, Coalfire disputes the latter claim—violated the terms of the get-out-of-jail-free letter. The sheriff also said the midnight assessment was a violation of a term spelled out in one section of the rules of engagement document. It said pentesting was to be conducted between 6AM and 6PM Mountain time. (Curiously, Iowa is in the Central time zone. Another term of the same rules of engagement (pdf) said physical testing “Can be during the day and evening.” Leonard wasn't aware of this last detail until I pointed it out in the interview. The sheriff has declined to release video of the incident.)

You’re going to jail

The get-out-of-jail-free letter “said you won’t manipulate doors,” Leonard said. “Well, they picked four doors. It said they won’t manipulate the alarm system. They went right up to the alarm and tried to shut it off. The biggest issue is they were only supposed to work from 6AM to 6PM. They came out in the middle of the night and broke in.”

Equally important, Leonard said, is what he believed to be the overstepping of Iowa officials who retained Coalfire. When the sheriff confronted the men that night, he said: "The State of Iowa has no authority to allow you to break into a county building. You’re going to jail.”

No one has more stake in the controversy than Wynn and De Mercurio, who risk being convicted of criminal charges that among other things could jeopardize government clearances and future job prospects. Coalfire CEO Tom McAndrew said in a statement last month that Leonard “failed to exercise commonsense and good judgement and turned this engagement into a political battle between the State and the County.” McAndrew also noted that Coalfire conducted an engagement for Iowa’s SCA in 2015 without incident.

Leonard said he has been receiving “hate mail” from as far away as Europe ever since the incident two months ago.

McAndrew told me that Wynn and De Mercurio did everything by the book. The employees, McAndrew said, intentionally tripped the alarm and then proceeded to the third floor to test the response. Crouching on floors or otherwise trying to be covert is standard practice after alarms are tripped to further test authorities’ response and see what surveillance cameras can detect.

A civil matter

Matthew Lindholm, the Des Moines defense attorney representing the two pentesters, agreed that his clients are being unfairly swept up in a power struggle between the State of Iowa and the County of Dallas. He said Iowa statutes ensure that the state judicial branch has access to county-owned buildings and that the judicial branch can exercise authority over county court houses when it’s necessary to carry out their administrative purposes.

Whether the state had authority to authorize the pen test is “a civil matter, not a criminal matter,” Lindholm said. “You’re not going to get that answer by filing criminal charges against somebody.” He also noted that a provision in the contract required the SCA to secure all necessary permission for the execution of the contract. Lindholm continued:

But you also have political pressures from the county who want to hold somebody criminally responsible because, it’s their opinion, that there clearly was no authority for the judicial branch to do what they did. The problem with that is under the legal analysis it doesn’t matter whether my clients had actual authority or apparent authority. As long as they reasonably believed they could go in and do what they did—which the contract said they could—they are legally obligated and cannot be held criminally responsible for doing what they did.

Dallas County Attorney Charles Sinnard, who is prosecuting the case, told me that prosecutors aren’t permitted to say much publicly about cases they bring. He did say that he was familiar with the craft of penetration testing and supported that line of work in ensuring courts are secure.

“I have a relative that is in the industry, so I understand the importance of the work, and I back that type of work,” he said. “Professionals in this area would also agree that there are certain responsibilities and expectations because of the sensitive nature of this work, and if those aren’t followed, then that is a different story. What has been released is only part of the story.” He didn't elaborate.

A mea culpa of sorts

In October, Iowa Supreme Court Chief Justice Mark Cady, who oversees the state’s judicial branch including all judicial officers and court employees, apologized for the incident before the state’s Senate Government Oversight Committee, according to the Des Moines Register, which has been closely following developments in the case.

“In our efforts to fulfill our duty to protect confidential information of Iowans from cyberattacks, mistakes were made,” he said, using the passive voice that’s so common in leaders’ admissions of responsibility. “We are doing everything possible to correct those mistakes, be accountable for the mistakes and to make sure they never, ever occur again.” He declined to comment for this story.

His apology made little or no mention of the two men whose futures have been swept up in the controversy. He has remained silent even after the release early last month of an investigation report the SCA commissioned from lawyers at Faegre Baker Daniels, a global law firm with an office in Des Moines. Attorneys who led the investigation into the matter included Nick Klinefeldt and Paul Luehr, a former US attorney for the Southern District of Iowa and a former federal prosecutor and a national cybersecurity consultant, respectively.

The investigators found that neither Wynn and De Mercurio nor Iowa's SCA acted with deception or ill-intent. The report also made a strong case that the pentesters had good reason to believe that everything they did was within the scope of the agreement between the SCA and Coalfire. The Rules of Engagement, the investigators found, specifically gave the men the authority to pick locks and to “utilize physical penetration testing techniques to gain access to facilities, sensitive information, networks or systems.” (The report did find that Coalfire and the SCA failed to adequately draft the agreement. More about that later.)

The rules of engagement also state that the physical assessments were to be conducted on the Polk County Courthouse and the Judicial building—both in Des Moines—as well as the Dallas County Courthouse in Adel, Iowa. And while one section of the rules of engagement was unclear whether the 6AM to 6PM time frame applied only to systems penetration or physical assessments as well, a Scope of Testing section within that document said physical assessments “can be during the day and evening.” That authorization made no mention of any specific time of day.

The investigators also mentioned that on September 10—one day before Wynn and De Mercurio entered the Dallas County Courthouse after hours—John Hoover, the IT manager for the SCA, found Wynn’s business card on his desk when he arrived at his office at the Judicial Building that morning. Hoover immediately knew the Coalfire pentesters had successfully broken into the building, and entered his office, the night before.

“Well done,” the IT manager wrote to Wynn in an email. “I'll be interested to hear how easy it was.”

Confusing and contradictory terms

The investigators went on to criticize both the SCA and Coalfire for stringing the agreement into three separate documents that “contained some confusing and contradictory terms” describing the work to be performed.

“In terms of techniques, the Coalfire agreement often co-mingled descriptions of physical tests with other types of assessments,” investigators wrote. “In its initial Service Order, Coalfire clearly described a plan to conduct ‘Physical Attacks’ against three proposed buildings, but in later forms, Coalfire’s Red Team activities fell under the more abstract label of ‘Social Engineering,’ even though a night-time building break-in would probably not involve social interaction with any other individuals.”

The permitted time for the pentesting is another example of a lack of clarity, with one section of the rules of engagement stating it would be conducted between 6AM and 6PM—again, in Mountain Time—and another section saying it could be during the day and evening. The lack of clarity in the get-out-of-jail-free letter was also a key problem, since that was the document responding Sheriff’s officials would read first.

Making matters worse, the investigators noted that there were differences among various SCA officials about precisely what the assessment involved. The IT director of the SCA, Mark Headlee, said he was unaware that the rules of engagement permitted the same physical assessment on the Dallas and Polk County courthouses that were allowed for the Judicial Building. While Hoover—the IT manager who had congratulated Wynn for accessing the Judicial Building—was more familiar with the scope of the engagement, a serious error prevented him from speaking to deputies the night they caught the pentesters at the Dallas County Courthouse. The report explained:

According to Headlee, it was his position that Wynn and Demercurio were not supposed to access courthouse after hours and so he told the Dallas County Sheriff Deputies that Wynn and Demercurio were not working within the scope of what SCA contracted with them to do. In subsequent text messages, Headlee questioned what Wynn and Demercurio were doing in the courthouse after hours. In text messages to Hoover, Headlee pointed out that the Dallas County Sheriff’s office did not believe the Authorization applied because the courthouse was county property. Hoover replied that he was just thinking about that issue. It appears neither law enforcement, Wynn, nor Demercurio contacted Hoover directly that night, because Hoover’s number was incorrect on the Authorization form.

Ultimately, the investigators found, it’s unclear if SCA had the authority to authorize the intrusions into the two county courthouses. While there are statutes that require counties to provide “sufficient facilities” for state judicial officers, it’s not clear whether this gives the SCA autonomy when state and county resources are commingled in a single premises.

Greatest shortcoming

Ultimately, the investigators said, both the SCA and Coalfire shared responsibility for not anticipating the way the assessment would affect the counties that owned and managed the courthouses and for not alerting law enforcement officers ahead of time.

“Perhaps the greatest shortcoming we found was a failure to take into account the potential impact of the assessment on third parties, specifically the counties,” the investigators wrote. “We did not find that the SCA or Coalfire acted with deception or ill-intent. “However, we believe both the SCA and Coalfire should have foreseen a potential confrontation with law enforcement.”

McAndrew, the Coalfire CEO, said his company is already looking at ways to prevent similar incidents from playing out.

“We could always improve,” he said when I asked him about that part of the report. “Every time we have one of these scenarios, you look at what could we improve in communication and what’s written down. We have looked at that and there are some tweaks to make.”

A mark on their record

Meanwhile Dallas County Sheriff Leonard has signaled an openness to recommending more leniency from the county prosecutor. In an interview, he said he had yet to read the investigators’ report that found the SCA had authorized a physical assessment in the evening and had approved the forced entry of doors. When I told him of those findings and asked if he still believed the county should prosecute the case, he said:

“If that is true, if those guys had all that, I don’t want them to have this mark on their record. They were nice guys that night.” Still, he returned to the position that the state of Iowa had no legal authority to grant the pentesters permission to break into a county courthouse. I pressed Leonard further and asked if, in light of the investigators’ findings, he believed the pentesters had any criminal intent. Leonard answered: “I don’t want these guys to have this mark on their record if they truly were supposed to be here.”

He went on to blame McAndrew, the Coalfire CEO, for not being more proactive in defending his employees in the hours following the arrests.

“The CEO could have called and said here’s all the stuff, Sheriff,” Leonard said, referring to the contracts Coalfire signed with the SCA. “Then I would have gone to the county attorney [Charles Sinnard] and said: ‘Listen, Chuck, you need to get rid of this stuff.’ They never did any of that.”

What seems clear from all of this is that for the time being, Wynn and De Mercurio will have these charges—and possibly new ones from Polk County—hanging over their heads, even though there’s no public evidence the pentesters had any criminal intent or bad motives. The ambiguous and sometimes contradictory terms in the agreement—which comprised multiple documents—was problematic. So, too, was the lack of clarity about whether Iowa’s SCA had the legal authority to permit an intrusion on county property.

But it’s hard to see how these defects rise to the level of a criminal offense that threatens not only the future of the two pentesters, but also the increasingly important profession of pentesting itself.

“If what is happening in Iowa begins to happen elsewhere, who will keep those who are supposed to protect citizens honest?” McAndrew wrote in his statement from October. “This is setting a horrible precedent for the millions of information security professionals who are now wondering if they too may find themselves in jail as criminals simply for doing their job.”

"how" - Google News

November 13, 2019 at 08:29PM

https://ift.tt/2q9CibM

How a turf war and a botched contract landed 2 pentesters in Iowa jail - Ars Technica

"how" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MfXd3I

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How a turf war and a botched contract landed 2 pentesters in Iowa jail - Ars Technica"

Post a Comment