In the past few years there has been an explosion of women’s writing. It’s a particular kind of writing that explores the politicisation of the personal, often blending with autobiography. While the essay form is usually considered to be objective, feminists have argued that the female subject has often been excluded from the picture and needs to be put back. Feminism is taking on and adapting conventional wisdom.

More like this:

- The genius who scandalized society

- What are fiction’s best first lines?

The old adage ‘the personal is political’ is finding truly exciting new applications. The feminist women’s essays of 2019 combine stringent forensic analysis with fearless movement in and out of autobiography. The personal is elbowing its way rudely into the discourse, and altering the definition of being rude. In the process, new kinds of personhood are being created.

As Rebecca Solnit says in The Mother of All Questions, 2017: “There is no good answer to how to be a woman; the art may instead lie in how we refuse the question.” Feminism is also increasingly agitating the status quo of masculinity, which is starting to seem like an untenable position. Take Solnit’s advice, and consider refusing the stupid, stultifying old questions.

In 2019 Rachel Cusk published a collection of essays called Coventry, which spans about a decade of her work. I have come to see each new publication by Cusk as thrilling. Although she is arguably a literary giant, she has won few awards, probably because she very wilfully sidesteps categories. (She once joked that she is getting accustomed to being a bridesmaid rather than a bride.)

Cusk is strongly emblematic. Her career began with a series of finely written and relatively conventional novels. But she really began to catch fire, in both senses, when she started writing autobiography. The first of these volumes was an honest look at motherhood. Really honest. She writes of “the sacking and slow rebuilding of every last corner of my private world that motherhood has entailed”. It got her into trouble for many reasons, but mostly for not being ‘motherly’ in the ‘right’ way. Volume two was a portrait of a woman on shaky ground masquerading as a superb work of art criticism. Volume three was an unflinching look at the aftermath of divorce, truly a sidestep too far. She writes that what others call “cruelty” she calls “the discipline of self-criticism”. The third book got such an ugly response that she mused about her “creative death . . . I was heading into total silence”. The cruellest of her critics accused her of being cruel.

Almost mockingly, in the Outline trilogy, her latest set of books, she embraces silence and passivity. Faye, the anti-heroine of those novels, is like a radio dish, absorbing everything around her in what has been called ‘violent’ detail, and giving almost nothing back. This non-personality throws everyone around her into relief, and especially men, who cannot resist a feminine vacuum. Faye is no-one, but Cusk’s life is woven into her in playful ways. No more presenting an easy target. In Coventry, the title essay of her book of essays, Cusk considers what it is like to be treated as a non-person, and decides there is liberation in it. In the Outline trilogy femininity implodes into a neutron star, invisible and exerting a pull on the essence of everything that approaches it. The effect is profound, dismaying, and liberating.

#MeToo was not the beginning of women speaking up, but of people listening – Rebecca Solnit

Rebecca Solnit, who published the collection of essays Whose Story Is This? in 2019, has been a superb essay writer for decades, and is certainly one of the most eminent feminist writers alive. She has written on many subjects other than gender politics; she is an environmentalist, political activist, art critic, historian. She is a genuine public intellectual. One of her better-known essays is the sardonic Men Explain Things to Me (2008), which gave rise to the term ‘mansplaining’.

Her anger seems to be modulating, maybe because feminism has made leaps of progress in the past few years. In the opening essay of her 2019 book, Solnit talks about how women have been negated and reduced to a footnote in the male story. The position that Cusk weaponises. Women are striving to take control of their own stories, to expand their personhood. “To change who tells the story, and who decides, is to change whose story it is,” she says. New stories are being born; but also, pivotally, new audiences. She observes that “#MeToo was not the beginning of women speaking up, but of people listening… One measure of how much power these voices and stories have is how frantically others try to stop them.”

Mirror, mirror

Speaking of which, Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, the New York Times journalists who broke the Harvey Weinstein story and helped catalyse the #MeToo movement, published their account of it this year as a book entitled She Said. They were awarded the Pulitzer Prize for their investigative work. The book is a detailed anatomisation of how Weinstein used the corporate and legal framework around him to silence his alleged victims, to “manipulate, pressure, and terrorise women” – but also how he attempted to use the same framework on the NYT itself, even up to the last moment. ‘Non-disclosure agreements’ are emerging as the legal vehicle of choice for male supervillains who want to de-personalise their female targets and stop them from telling their stories. That lid, and many others, blew off volcanically on social media.

The word ‘confessional’ is often trotted out, as if the personal mode is a sort of confession of sins, like a purging

Irish writer Emilie Pine’s unassuming courage and clarity of thought has enchanted me. Notes to Self is her book of “personal essays” that critics have heaped superlatives on – they said it would make me cry, and it did. She resolves to write about things “you never tell anyone”, to invite us deep into her head, and yet somehow she holds the ship steady. In a chapter on her self-centred, self-destructive father, in whose orbit she has been trapped for most of her life, she comes to a realisation: “I need to write my own narrative”.

Pine’s words are transformative. The word ‘confessional’ is often trotted out at these moments, as if the personal mode, and especially the one in recent use by women, is a sort of confession of sins, like a purging after which one can wipe one’s mouth and get on with the day. But Pine doesn’t want to expiate her sins; she is annexing the hidden parts of her story and giving herself permission to live in them.

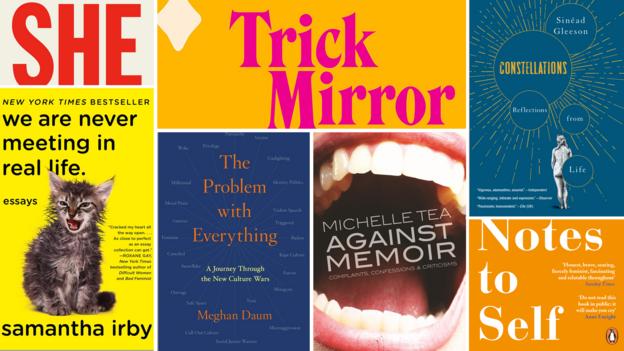

By far the most exciting essay collection I’ve read this year is Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion. She is a 31-year-old US-Filipino millennial who has worked for feminist websites like The Hairpin and Jezebel, and now writes for The New Yorker. She brings her exceedingly powerful mind to bear on problems of identity, particularly those associated with late capitalism and the internet. Her signature approach is to dig into things (the architecture of the internet, female self-optimisation as a form of marketing, the US’s scam culture), and nuance them relentlessly. Although she is a digital native, and up to her neck in social media, she has also said that she put a blocking app on her phone that prevents her from using it more than two hours a day.

If feminism this year was about letting the personal into the political, then Tolentino questions how the personal is constructed in the digital age. Is sharing the personal on social media really being personal, or just corporate manipulation? Is #MeToo also partly a phenomenon created by the trick mirror of the internet? How are we encouraged to package and perform ourselves, and for whom? From her point of view, feminism is in danger of being reduced to “ideological pattern recognition”.

Tolentino refers to “this dead-end sense of my own ethical brokenness”. The challenge as she sees it is to navigate through the millennial experience. She doesn’t seem convinced that the world can be fixed, though her unstoppable intelligence and gallows humour say otherwise.

There were many other extraordinary women’s essay collections published in 2019: all are intensely ‘personal’, but it is personality as a process of radical re-definition. Michelle Tea is a fierce, elemental, foul-mouthed intelligence on the loose, and she pulls us after her in Against Memoir. The title is ironic: at one point she talks about getting interested in Buddhism but then realising this involves negation of the self, she observes: “I refuse to drop my storyline”.

Samantha Irby runs the torrential blog Bitches Gotta Eat, and writes about her life, transmuting gold into even more gold. Her collection of essays, We Are Never Meeting in Real Life, is grounded, hilarious, and diamond sharp. Last but not least, Meghan Daum’s The Problem with Everything is an entertaining collection of essays about the culture wars, and about how identity politics is beginning to eat itself. Only Daum would have the courage to write a book like this – she’s a free thinker in the truest sense, a master of the unspeakable (the title of another of her collections).

And with a synchronicity that can’t be accidental, Penguin this year reissued Sister Outsider, a collection of Audre Lorde’s essays. She described herself as a “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet”, and firmly grounded her politics in personal honesty. Her strange, lyrical, visceral prose defines her as one of the gods of feminism and political activism. In one of her essays she asks, “How do you use your rage?”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"how" - Google News

December 17, 2019 at 05:01PM

https://ift.tt/2EmVJRY

Essays by women: 'How do you use your rage?' - BBC News

"how" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2MfXd3I

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Essays by women: 'How do you use your rage?' - BBC News"

Post a Comment