Three days ago, I received the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. As a pediatrics resident working in New York, I saw it as a glimmer of hope during an otherwise bleak winter. Before administering the shot, the nurse described the possible side effects and confirmed that I had no allergies. Then she asked what seemed like the next in a series of mandatory questions: Did I want to take my own picture while getting the vaccine, or should she ask someone else to do it?

“Vaccine selfies” have become ubiquitous on social media, but I was initially reluctant to share mine. Many people are (justifiably) disappointed that they have yet to gain access to the vaccines. While almost 10 million doses have been distributed in the United States to date, frustration about the rollout is growing, worsened by images of those who appear to have “jumped the line.” Meanwhile, COVID-19 deaths continue to mount, with more than 375,000 lives lost in the U.S. But before long, the vaccines will be available to the general public, and the biggest obstacle in the COVID-19 vaccination effort will eventually shift from distribution to skepticism. When that moment arrives, every photograph of someone receiving a shot will be a much needed vote of support.

Vaccine photography has a long history in public-health promotion efforts. Following the development of the first vaccine against polio in 1953, Jonas Salk was photographed administering the still-experimental shot to his family. The renowned scientist Maurice Hilleman continued the tradition when he developed the first mumps vaccine in 1967. His infant daughter was photographed as one of the first children to receive it. Having developed the immunization using a throat swab from his older daughter, Hilleman later commented that this was a unique event in the history of medicine: “a baby being protected by a virus from her sister.”

Several years after Salk, Albert Sabin developed the live-poliovirus vaccine, which was delivered via a teaspoon of cherry-flavored syrup rather than a needle. (Sabin’s vaccine would later serve as inspiration for the song “A Spoonful of Sugar” in Disney’s Mary Poppins.) Over the span of a few weeks in 1960, more than 100,000 schoolchildren lined up to receive Sabin’s vaccine at hundreds of clinics across Cincinnati. Photographs of these events, published in newspapers around the world, helped popularize the image of a vaccine in high demand.

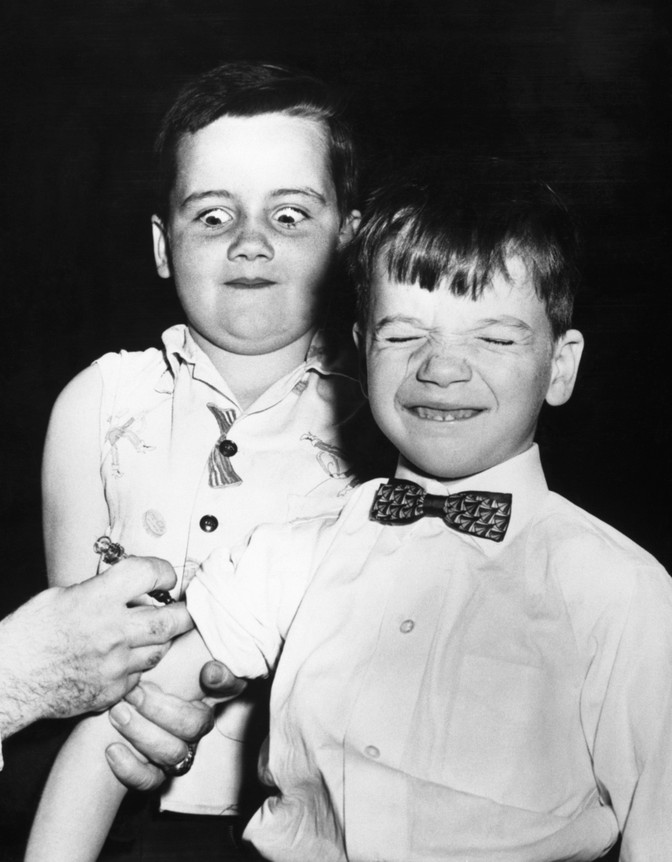

Photographs can be persuasive tools in overcoming skepticism toward the science of immunization itself. A striking image from a 1901 medical textbook depicts two 13-year-old boys shortly after they were accidentally exposed to the smallpox virus, one of whom had been vaccinated against smallpox in infancy. In the photograph, one face is clear, while the other is riddled with pox. “It’s an image of the consequences of being vaccinated versus not,” says Kathleen Bachynski, an assistant professor of public health at Muhlenberg College, in Pennsylvania. This photo was effective, she notes, precisely because smallpox was such a disfiguring illness. Smallpox exists now solely in photographs: It is the only disease to have been completely eradicated by vaccines. This crowning triumph for public health also highlights the challenge of conveying immunization’s merits in photos. The success of vaccines is defined by the absence of illnesses that previously ravaged the globe; their benefits are, quite literally, invisible.

Images frequently accompany news stories about vaccination, but by default they tend to depict the act of immunization, featuring large needles and crying, distraught children. The overwhelmingly negative emotions these photos elicit—disgust, anxiety, fear—might subtly alter public feelings toward vaccines. There has been a push in recent years for journalists and editors to select photos that accurately highlight the result, rather than the process, of inoculation: pictures of smiling, healthy children and adults.

The choice of which images to publish is significant. Vaccine-related information on Twitter is twice as likely to be shared if it includes an image, and a picture often sets the tone for how such messaging is received. But responses aren’t straightforward: In one study, parents who were shown photographs of children sick with measles, mumps, or rubella were more likely to believe that vaccines have dangerous side effects. Researchers speculated that images of illness, even when intended to demonstrate the consequences of not vaccinating, could unintentionally strengthen associations of vaccines with being sick. Conversely, COVID-19 vaccine selfies—which highlight health, joy, and optimism—could positively shape the public response to the vaccines.

Trusted public figures who are eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine might also help promote confidence by sharing their own selfies. President-elect Joe Biden received his two doses on live TV. Celebrities in eligible groups, such as Sanjay Gupta and Ian McKellan, have also begun posing for photos while getting their shots—a tradition with historical precedent. In 1956, a 21-year-old Elvis Presley, then at the height of his fame, was photographed as he received the polio vaccine, resulting in renewed public enthusiasm for the shot. This photo was compelling, Bachynski points out, not only because Elvis was a celebrity, but also because he appealed to teenagers who were both at risk of the severe effects of the poliovirus and reluctant to receive the vaccine.

Last week, Baseball Hall of Famer Hank Aaron and Black civil-rights and health-care leaders were photographed receiving a vaccine at Morehouse School of Medicine, a historically Black college. This event highlighted the potential power of vaccine photography to reach people who are disproportionately hurt by the pandemic. Black, Hispanic, and Latino communities have been devastated by the coronavirus, with rates of infection and death significantly higher than those in white communities, reflecting inequities in health-care access and socioeconomic status, as well as the effects of systemic racism. Because medical institutions have repeatedly violated the trust of these communities through atrocities such as the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, Black and Hispanic populations have also reported a lower likelihood of accepting a COVID-19 vaccine than white populations.

Undoubtedly in recognition of this fact, the first COVID-19 vaccine administered in the United States was given to Sandra Lindsay, a Black critical-care nurse who received the shot on camera and said she wanted to “inspire people who look like me.” “It is important for individuals from Black and Hispanic/Latinx communities to see others, especially those who look like them, getting this vaccine,” says Kristamarie Collman, a family physician in Florida who addresses COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on social media. Vaccine selfies allow information to be shared in a personalized and relatable way, Collman says, adding that intra-community conversations about immunization are also crucial to building trust.

Humans are hardwired to respond to visual images, which capture our attention and burn in our memory far more vividly than text alone. The thousands of photographs of health-care workers beaming into the camera lens or shedding tears of joy and relief offer a profound emotional counterpart to the overwhelming statistics of the pandemic. For decades, anti-vaccine groups have relied on the power of personal narratives to bolster claims of vaccine danger. Vaccine selfies, accompanied by captions offering moving anecdotes or thoughtful reasoning, provide a fitting and necessary counterargument. Collectively, these images might strike a chord with the nonmedical public in a way that data-driven discussions of vaccine efficacy and infection rates cannot.

The challenges facing a woefully unprepared nation attempting to undertake a massive vaccination campaign are real and disheartening. But widespread vaccination is the only realistic path to recovering some semblance of the lives we had before. The vaccine selfie may seem like a relatively modest endeavor in the public-health effort against COVID-19, but together the people posting these early images share a formidable message: We believe in this so strongly, we’re not only volunteering to go first, but are thrilled to be given the chance.

"share" - Google News

January 15, 2021 at 01:28AM

https://ift.tt/2LOG5Wz

Go Ahead, Share Your Vaccine Selfie - The Atlantic

"share" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VXQsKd

https://ift.tt/3d2Wjnc

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Go Ahead, Share Your Vaccine Selfie - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment